Took a trip to Knoxville yesterday. The whole city was shot full of people. Traffic was thick.

But I've never before seen so much courtesy in a town full of drivers. Several times, people stopped to let me turn into the traffic. Found myself doing the same for others. It was like we had a collective understanding that, "Ok, we're all in this together, so we'll make the best of it." I was really impressed. Good job, Knoxville.

Now, was all this courtesy due to Southern hospitality or was it "Christmastime in the city?" Did the season afford us "peace on earth, good will toward men" at traffic lights?

What did the messengers mean when they first proclaimed, "Peace on Earth, Goodwill Toward Men?"

Well, "Peace on Earth, Goodwill Toward Men" is not the basis of a Coke commercial where we sing together at a candlelight vigil and pause for refreshment and group hugs.

The peace expressed that first Christmas night was

God's goodwill toward humanity. Why would it be so remarkable a statement?

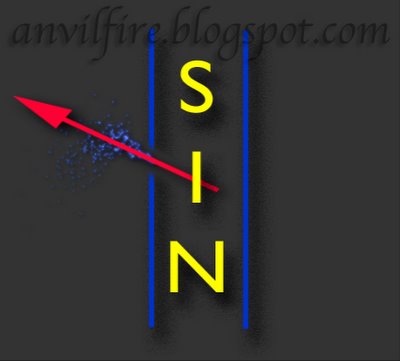

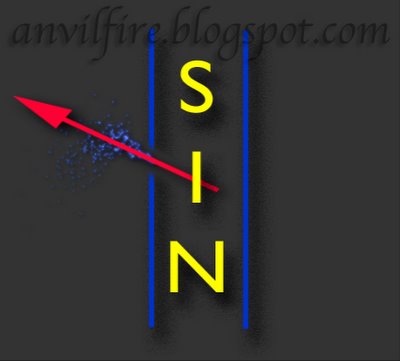

Because men are sinners and rebels against this good, holy God.

God created man to be in perfect fellowship with Him, but we spurned Him and chose our own way. We established hostility toward God in our hearts. And we see it everywhere.

There is much to show that God made obedience easy. He created man without a sinful nature, placed him in an ideal environment, provided for all his temporal needs, endowed him with strong mental powers, gave him work to engage his hands and his mind, provided a life-partner, warned him of the consequences of disobedience, and entered into personal fellowship with him. Surely, God cannot be blamed for man's apostacy. - Henry Theissen.

We are foolish enough, in the midst of all this, to believe that we actually have a case against God. We blame Him. We blame others.

We want to blame crime on poverty. We want to blame child abuse on one's background. We want to blame terrorism on the existence of capitalism and a free society... The list goes on and on... I am not saying that environment has no influence on people, but it is never a

root cause. We must take personal ownership of our transgressions, because sin is a willful transgression of the law. We established "enmity" against Him in our hearts.

I cannot place the blame for my particular set of sins on anyone else: It falls to me.

Until a person recognizes that his sin problems are rooted in

rebellion for which he or she is morally responsible, there is no hope for that person to be released from his or her bondage. It is a problem between the person and God.

"Because the carnal mind is enmity against God: for it is not subject to the law of God, neither indeed can be, So then they that are in the flesh cannot please God." -Romans 8:7C.S. Lewis put it to a point when he mentioned that

man is not simply a weak creature who needs rehabilitation. He is a rebel who must lay down his arms.

The wonderful scandal of it all is that God justifies and forgives rebels--at a high price to Himself: the sending of His Son.

"Peace on earth, goodwill toward men" is not referring to a heart-felt cry for human to human reconciliation, or courteous driving, as nice as those things are.

"Peace on earth, goodwill toward men" is the great truth that God is willing to be reconciled to rebels who have dishonored His glory and had murderous intentions toward their Creator.

Christ Himself is God's goodwill towards men.

Christmas launched the ministry of reconciliation in the life of the Messiah.

Amen.